Gentle reader,

We’re prone to embroidering shrouds with false and flimsy ghosts, prone to telling untrue stories of our dead, rewriting them in our own image or in the image of some saccharine version of sanctity.

But the dead are flesh and bone, and that flesh and bone is beloved of God, who made flesh his own, for our sake.

Very truly I tell you, unless a kernel of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains only a single seed. But if it dies, it produces many seeds (John 12:24, NIV).

On the day we buried my Grandpa Felker, his children—my father and his siblings—planned a detour between the funeral home and the cemetery.

The funeral procession would drive past the family farm; we’d all honk our car horns when we passed by, a rendition of taps: noisy and amelodic but nonetheless heartbreaking.

It’s been our family’s farm since 1863.

“In honor of Indiana's rich agricultural heritage, the Hoosier Homestead Award Program recognizes families with farms that have been owned by the same family for 100 years or more.”

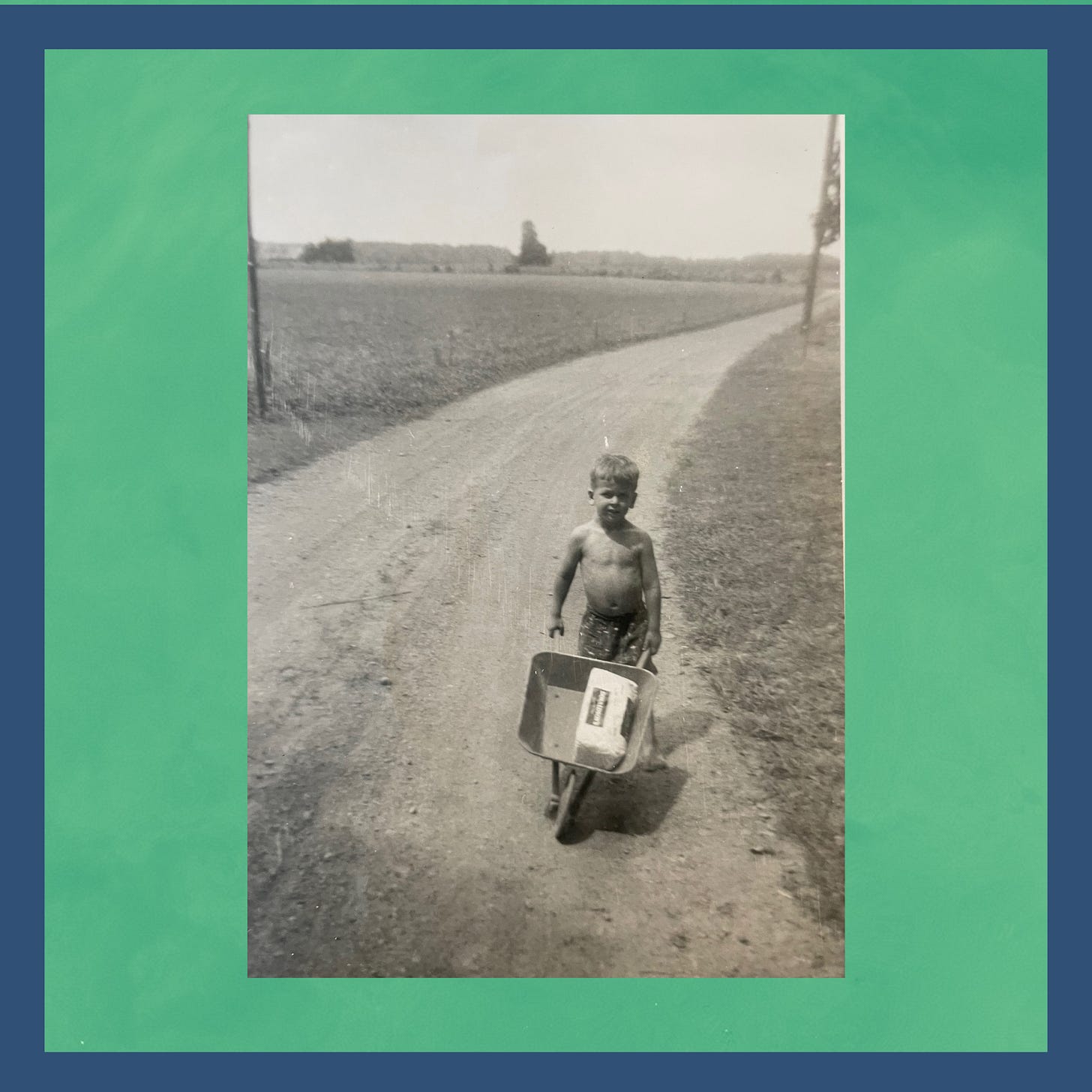

Our farm received the Hoosier Homestead designation in 2001, right around the time it became clear that the next generations would not continue farming that land. Grandpa was 79, still getting out on the tractor, arms sun brown to the place where a work shirt ends, then pale, like a fish belly, freckled with time. (“For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim, Praise him!”) You can’t hardly get a good pair of work jeans anymore, he said.

If for this life only we have hoped in Christ, we are of all people most to be pitied (1 Corinthians 15:19, NRSVUE).

Dad was raised on the farm. The morning after senior prom, he still had to get up at 4am for milking. Those cows are long gone, though they moo at the very back of my memory, mixed with stink and dirt and blood. Dad still won’t drink milk, though he’ll put it on his cereal.

He’s not old enough for this to be the case, but he grew up with an outhouse. They tore down the old homestead and built the new brick house, with the indoor plumbing, when he was a child.

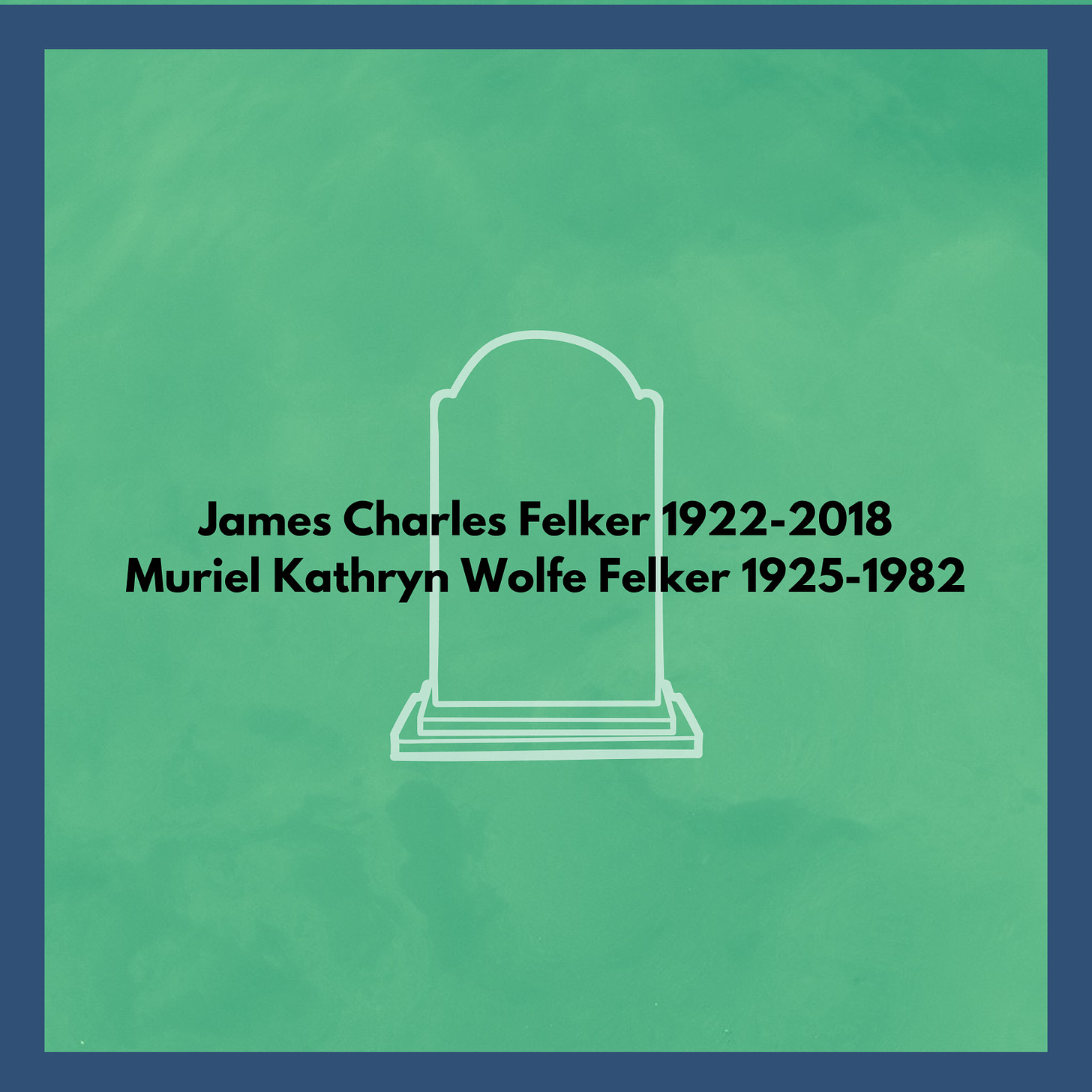

My grandma’s name was Muriel, but she was always called “Merle.” Merle couldn’t have been sorry to see the old house go. I guess it was the one she’d come home to, as Jim Felker’s bride, displeased to find the stove was wood burning, where she’d been used to better.

The Felkers are not early adopters.

Can you imagine trying to get the flame right to set your stew to simmer on that wood burning stove? In my gut, I feel how heartily grandma must have welcomed her new kitchen and her new toilet too.

She gave my mom a toilet brush for Christmas once. Merle wasn’t always an easy woman.

She played the piano. My dad bought a baby grand with the money that came to him when she died. She went to college for a year. I imagine she was called to preach, but her work was turned to farm and family instead. Her basement was full of the yield from her canning, glass jars tottering on dusty shelves. Fruitful but pickled. Both things can be true. I loved her, and she loved me.

I asked grandpa why he married her. Well, he just liked the look of her, I guess. He laughed.

Now if Christ is proclaimed as raised from the dead, how can some of you say there is no resurrection of the dead? If there is no resurrection of the dead, then Christ has not been raised, and if Christ has not been raised, then our proclamation is in vain and your faith is in vain (1 Corinthians 15:12-13, NRSVUE).

When we visited as children, we’d run wild, hunt crawdads in the creek, climb into the hay loft and roll around with the kittens, balls of fur still too new to have yet turned mean from farm life. Golden with hay and sweat, we’d come back inside and my uncle, the ornery one, would rile us up even more.

Oh, the surprised sting of his rebuff when, at grandma’s funeral, he brushed off my attempts to play.

I would have understood, but I knew the funeral was a ruse. Just a trick to get me there for my surprise party. But it wasn’t a trick. The cancer won out, and my grandma went into the ground. Funerals are no respecters of birthdays.

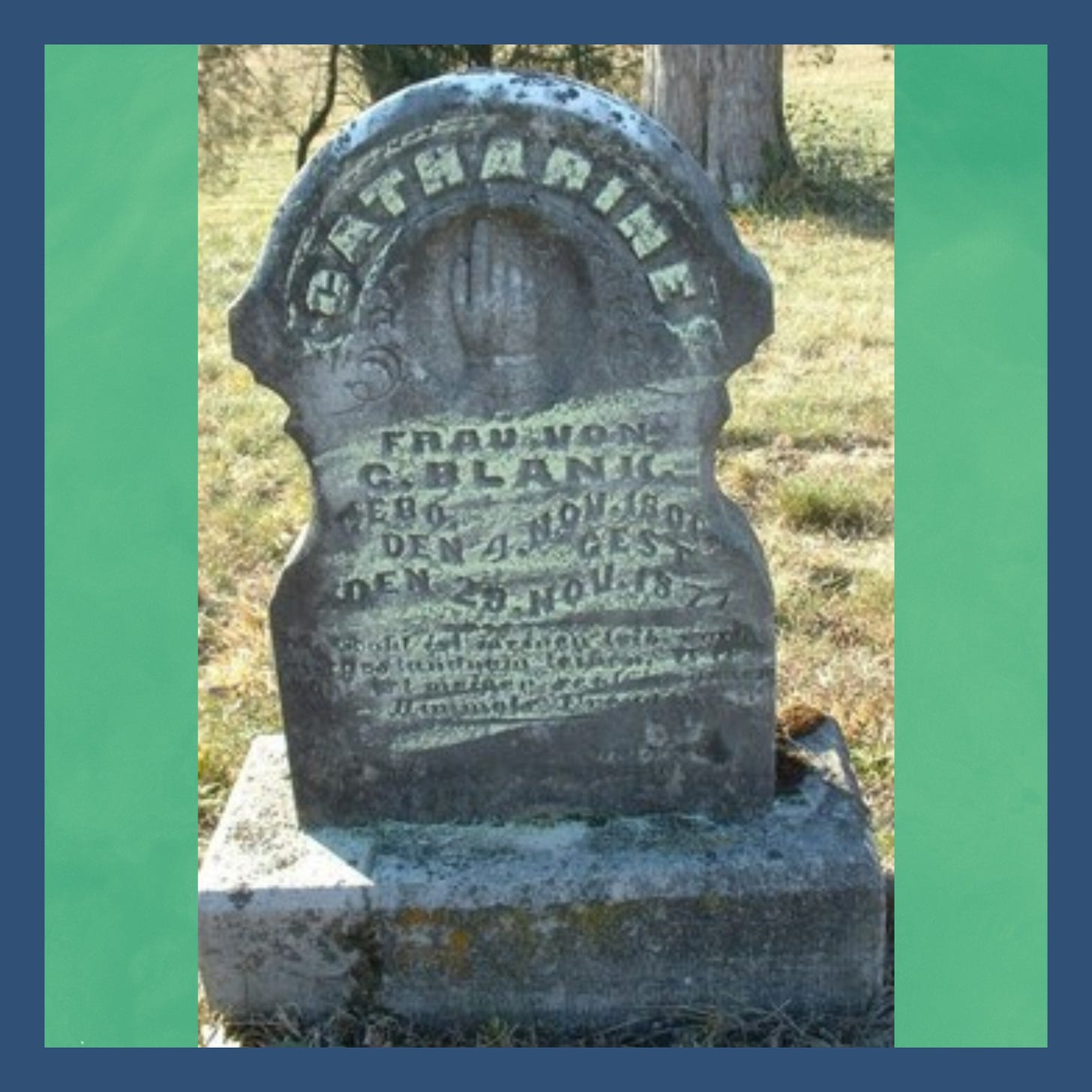

The very first of the Indiana Felkers—they were still Voelkers, then, “the people,” my people—are under the roadside earth in a little family cemetery: predating burial regulations, I suppose.

… as all die in Adam, so all will be made alive in Christ. But each in its own order: Christ the first fruits, then at his coming those who belong to Christ (1 Corinthians 15:22-23).

Those first gravestones are auf Deutsch, predating the wars that would make the language verboten, predating that second war which would make grandpa’s speech so spare. (I like to imagine he talked more, before. This is probably false. He was a quiet man. But there was a special quiet around any chance for talk of the war).

I imagine him, first time he stepped outside Harrison county, finding himself on the other side of the sea. That land, too, held the old bones of his people, but those must have been crumbled near to dust by that time. He was a pacifist. I know the war did that. I loved him, and he loved me.

Grandma’s bones would lie alone for a spell, before grandpa’s finally joined her. 36 years between those losses. Merle’s youngest, her only daughter, gone from a girl of 19 to a woman of 55, time enough to take on her mother’s wild gray. Time for the granddaughter on whose fifth birthday she was buried to begin her own wolfish graying.

432 months. More than 157,000 days. A long time. A mere few breaths. 36 years couldn’t undo the power marriage wielded to keep my grandpa’s bones out of the Lutheran cemetery where his parents sleep. Their son’s wife was a Methodist, and he would lie among the Methodists too.

They’ll rest together and rise together, as they did all those nights in two stiff twin beds and all those early mornings when the needy cows would allow no lie in. Fruitful but pickled. Both can be true.

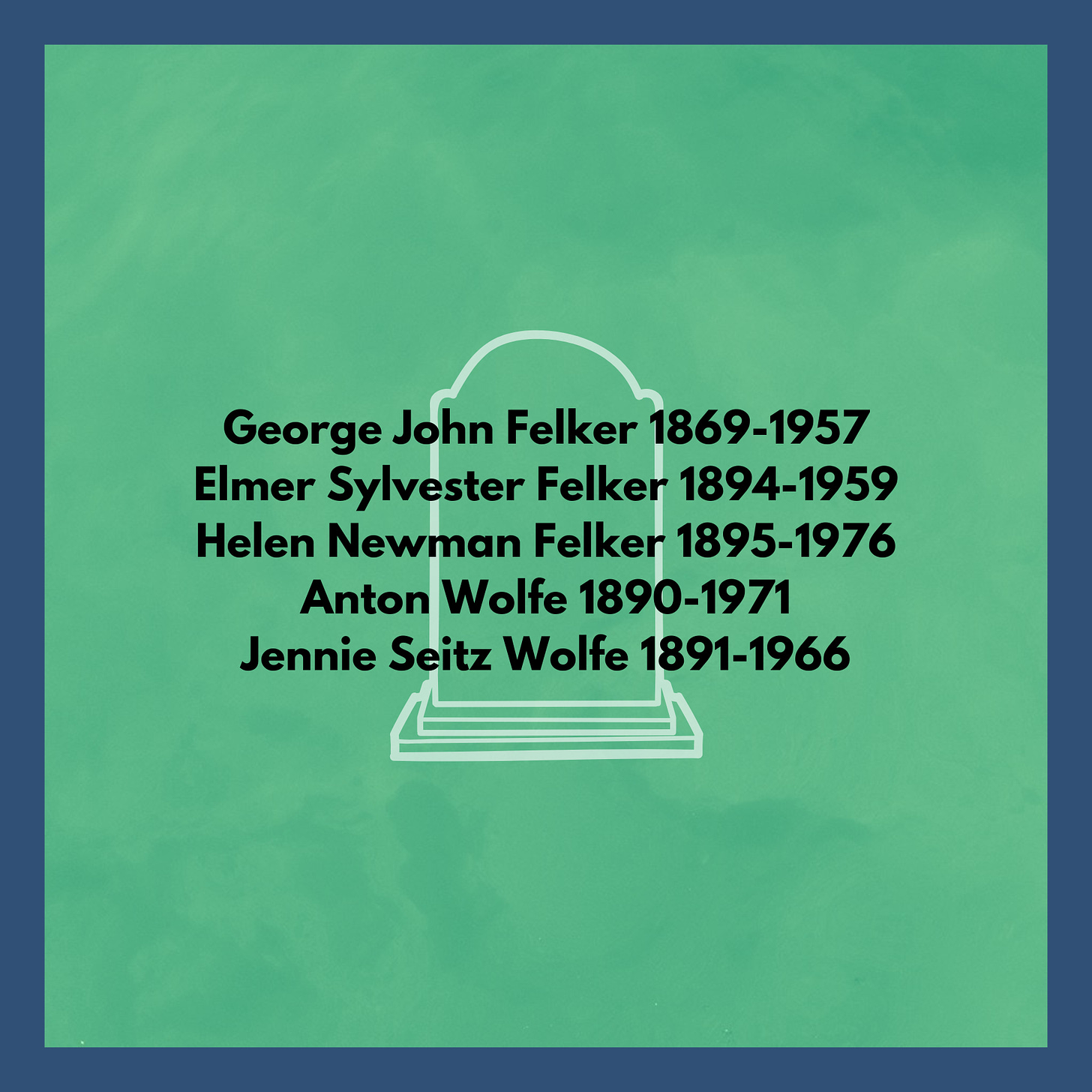

His parents and grandfather are buried over at St. Peter’s Lutheran. All the cemeteries are right there, in Harrison County, so the distance isn’t far. Merle’s parents aren’t far either, in the Methodist Cemetery over in New Middleton, still in Harrison County, where they too were born. Roots of the same trees wrap up the Lutherans and the Methodists together in one cocoon.

The bones of my dad’s people cluster in that county.

How different confessing the resurrection of the flesh must have felt. When your people have been in this same place ever since they came from across the sea, when they’ve stayed put and intermarried here, farming this land until their bones went into this ground.

(No nostalgia here. Harrison county, Indiana is no kingdom come. I just note the distance between them and me. How it must have felt, to work the land seeded with the bones of your flesh and your blood.)

But someone will ask, “How are the dead raised? With what kind of body do they come?” Fool! What you sow does not come to life unless it dies. And as for what you sow, you do not sow the body that is to be but a bare seed, perhaps of wheat or of some other grain (1 Corinthians 15:35-37).

I don’t know where I’ll be buried. I’m trying to build a story out of scraps. The flesh I have for these bones is sparse. But not too sparse for love.

You know those long genealogies in the Bible? How good preachers tell us that they matter, they’re not boring, they’re the very flesh and bone history of Christ our God?

I don’t claim the gravitas of scripture, but my people’s bones are part of that same history, even though I only have some names and dates and the knowledge that they’re nestled under the good Indiana earth.

Voelkers and their kin packed up house in Germany and unpacked in Harrison County. Together, more or less, in time and place. They left the bones of their dead behind on the blurry French-German border and made babies in the rolling hills of Southern Indiana, which maybe looked like Germany, through the sunlit haze.

So many babies. Susannah, for instance, birthed Elizabethe in 1846, Heinrich in 1847, Marie and Amalie in 1851. With her husband, she bundled the still living children across the ocean, where she would have William in 1853, Johann in 1855, Johannah (my great-great-grandmother) in 1860, Fritz in 1864, and Sophia in 1867. Nine babies and her husband dead when she was 48. I’ve never met Susannah, but I feel her flesh. Nine placentas. Nine umbilical cords. Nine times her milk came in and nine times the children were weaned.

Just as we have borne the image of the one of dust, we will also bear the image of the one of heaven (1 Corinthians 15:49).

A whole pack of distant cousins—cousins to one another and to me—made the trip. I don’t know why. Sorrow? Hope? The internet unearths a few names. Born in Germany, mostly around the one small town, dead in Harrison County. Grandma’s Wolfes and grandpa’s Voelkers there together, in Mensfelden, going back to the 17th century. We can trace the Voelkers ten generations back to Fritz (1674-1722), whose dates we have, and his folks, Friedrich and Auguste, who are only names and long leached bones.

For this perishable body must put on imperishability, and this mortal body must put on immortality (1 Corinthians 15:53).

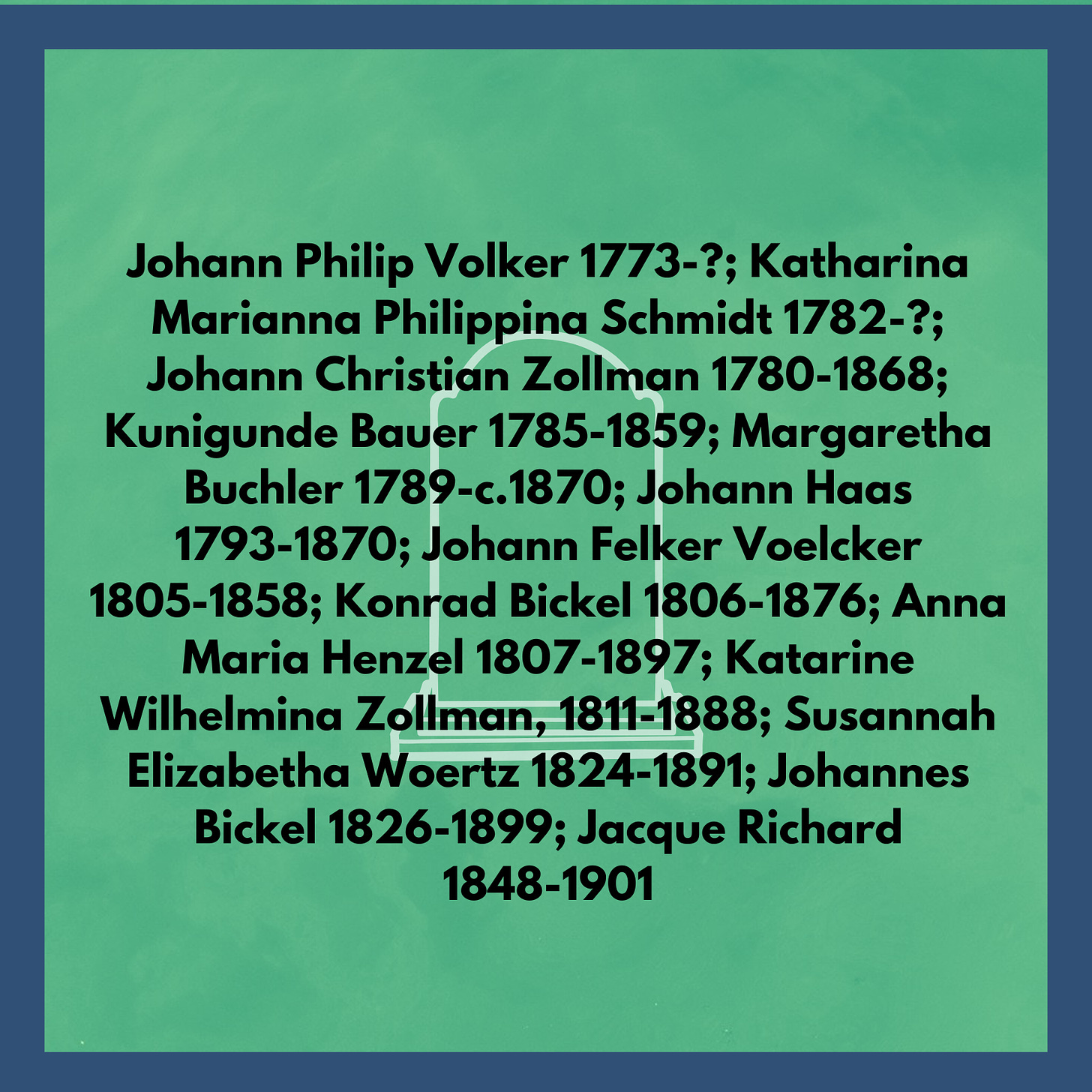

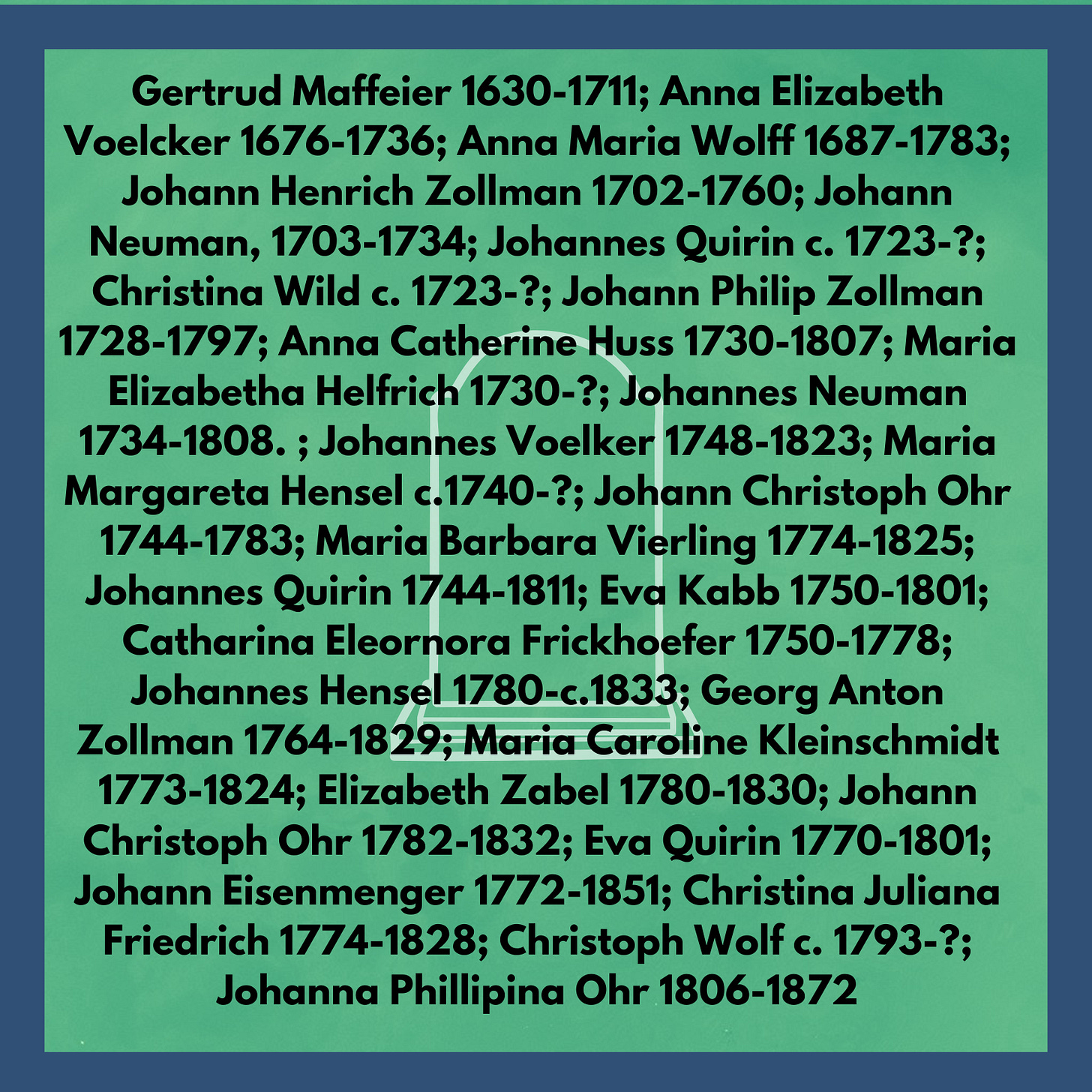

Some of those who made the journey.

And some whose bones still lie in Germany.

On the day we buried grandpa, as the funeral procession went to make that last pass by the farm, we got stuck behind a manure spreader. We were stuck for quite a spell, creeping down the narrow rural roads.

Behold, the parade to the cemetery, led by a crawling fertile stink, followed by a chain of Toyotas and Chevys. Grandpa drove American cars. Until he didn’t anymore.

The manure spreader? Dad thought grandpa would have liked it.

Banish the whitewashed ghosts. God loves us flesh and bones.

Don’t fear owning the procession to the graveyard, where fertile stink goes to ground, trusting God will gather it up again, safe against that glorious day.

“Death has been swallowed up in victory.”

“Where, O death, is your victory?

Where, O death, is your sting?” 1 Corinthians 15:55.

Grace & peace,

BFJ

If this piece has been good to you, I’d be grateful if you’d forward, share, and subscribe.

What a small world we live in! I followed the recommendation from Kristen Du Mez to check out your writing. Wow am I glad I did! I'm sitting in my home in Australia, writing a prayer for a memorial service that will take place in my hometown in Orange County, Indiana this weekend! Your words and pictures transported me to my own childhood in the hills of Southern Indiana. Thank you. Peace and grace to you.

What a gift.