Questions about hell

On assurance, apokatastasis, annihilation, human immortality, eternal conscious torment, and the God Who IS Love

Gentle reader,

I recently solicited questions you’d like me to address here at Church Blogmatics. A group of those questions cluster around Christian teaching about hell, a teaching which is very difficult for many of us. In today’s post, I’ll try to take those questions on (though each question could merit a much longer answer).

As a teacher, I usually have relatively little to say about hell. That is, I want my students to focus instead on the center of the shared riches and wisdom of the Christian faith, and—on my reading—that means focusing mostly on who God is (Father, Son, & Spirit), who Jesus is (fully God and fully human), and on God’s transforming relationship with us.

In some ways, hell is a side doctrine. There is not (nor has there ever been)1 broad theological consensus on answers to the questions below. Focusing on the center of the faith, though, will help us do better thinking about hell. If we think we know the truth about hell, that truth had better correspond with what we know about the God who is love. (That is, whatever we believe about hell has to be determined by who we know God to be in the person of Jesus Christ.)

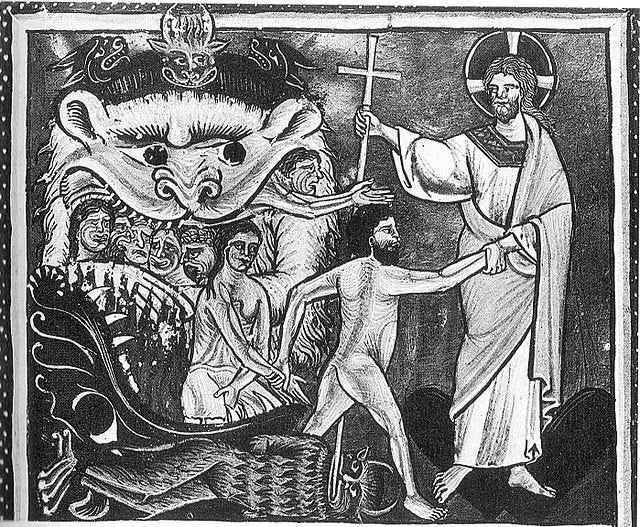

Jesus opening the gates of hell and releasing those imprisoned there (1 Peter 4:6), portrayed in many images of the “Harrowing of Hell,” Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

By the time the Protestant Reformers entered the scene, Western Christianity (Roman Catholics and those who would become Protestants) teaches what you’ve probably been taught about hell: that it involves eternal punishment and (surprisingly) that we have a pretty good idea who will land there.

Late medieval Catholic piety understood one’s eternal fate to be sealed at the moment of death. Folks wanted to die in a “state of grace,” (having received absolution, through the church, from mortal sin), and reception of sacramental last rites was understood to assure that “state of grace.”

Most people would have believed that they constantly shuffled back and forth between being saved and being damned and that churchly sacramental intervention could restore one to salvation. The cycle was understood to go like this:

a) you’re baptized into a state of grace —> if you die now, you’re saved…

b) you commit a mortal sin (one bad enough to cut you off from God; we all commit lots of these) —> you fall out of the state of grace and into a state of mortal sin; if you die now, you’re going to hell…

c) you receive absolution through the sacrament of penance (confession) and are returned to a state of grace…

d) the cycle repeats; state of grace —> state of mortal sin —> state of grace —> state of mortal sin…

e) when death is near, you receive last rites (final absolution from sin, with confession, repentance, and anointing), assuring that at death your soul is in a state of grace.

(There was no sense of security or assurance here: every new act of mortal sin puts one back in need of the sacrament of penance and absolution.)

Protestant theology intervened in this system, teaching that, because Christ died once for all, his atoning work covers all our sin, forever, because we are in relationship with him. The medieval peasant no longer needed to worry about dying without last rites and so being condemned to hell. (The plague meant that lots of people died without last rites, and this was a motivation for conversion to Protestantism.) The Reformers taught a hell similar to the Catholic one, but Protestants could now rest assured that they’d been saved from it.

In theory. Because Protestants didn’t stop using the idea of hell as a terrorizing threat, and Protestants held on to the idea that we can basically understand who is saved.

My hypothesis about the whole thing is this: the Protestant reformers were right, here, but they didn’t go far enough in breaking the mechanistic understanding of salvation they’d inherited. That system remains largely intact, allowing later Protestants to approach evangelism from a perspective which claims to understand and control salvation nearly as much as the late medieval Roman Catholic church had done. (Altar calls replaced the confessional? Can I say that? I said that. I’ll say more about this hypothesis in my forthcoming book from Intervarsity Press, Why I Am Protestant.)

The questions:

(Thanks to the readers who submitted these questions! I’ve shortened or paraphrased original wordings).

For those who wrestle with sin after entering into a relationship with Christ, is there any assurance and hope that they have not strayed too far? How do we hold together biblical passages which imply that our salvation is secure in Christ with those passages that emphasize the danger of persisting in sin?

Short answer: is there any assurance? Yes. Are you choosing to reject Christ? If not, then be assured that you remain in saving relationship with Jesus.

This question gathers up many of the mysteries of salvation! Can we “lose” our salvation? Can we know that we are “still” saved, even if continue to sin? Here, we run up against the great question of the relationship between faith and works.

Here’s what we can say for sure:

salvation is a free gift in the grace of Jesus Christ, which means we can neither earn it nor “unearn” it.

scripture is clear that when we are in Christ, our lives will be changed. We will begin to be transformed, to know freedom from sin.

But our freedom from sin will not be complete in this life, and this must mean that new instances of sin cannot cancel out our salvation, so long as we remain in relationship with Jesus Christ.

The danger here is “cheap grace,” the idea that we can happily sin, without consequence, because our salvation is assured. But vital relationship with Jesus Christ simply will not allow cheap grace.

I do believe (though the language is clunky and points to a mystery beyond itself) that we can “lose” salvation, but that loss would not come because we continue to sin. That loss would come only in rejecting Christ. To be “in Christ” is to be saved, full stop, and that salvation is worked out in our lives—usually slowly and by degrees—as we begin to gain victory over sin, a victory that will only be full and final in the kingdom yet to come.

That is, I’m not going to hell if I tell a lie. That doesn’t make truth any less important, but it does mean that “in Christ” my salvation is assured.

I may make some of my fellow Wesleyan-Holiness folk nervous here. (The Wesleyan-Holiness tradition emphasizes the need for transformed lives and is optimistic about what God can do to change our lives), but the Wesleyan-Holiness tradition is still a Protestant one, and I’m convinced that the only healthy way to look for holiness is from a place where one knows safety and assurance in belonging to God.

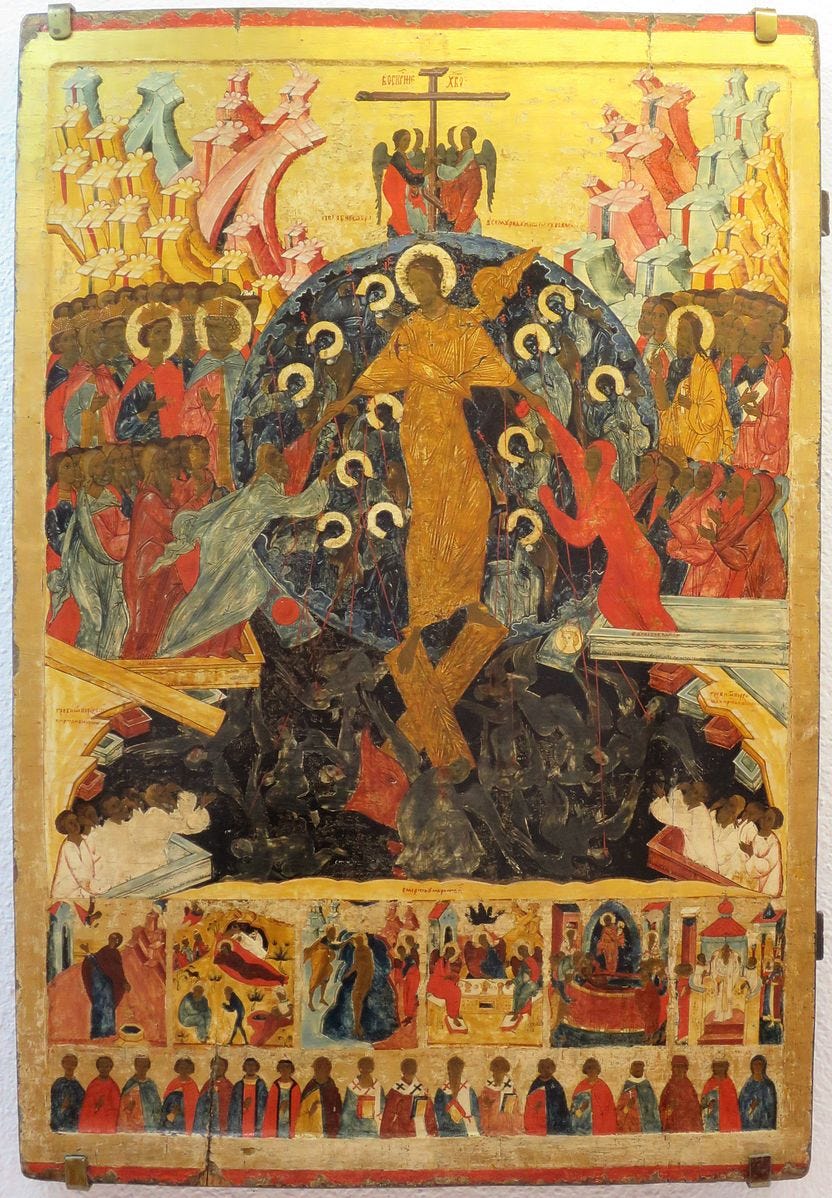

Russian icon, Resurrection - Descent into Hell, with Feasts and Selected Saints, first half of 16th century, Solvychegodsk, Arkhangelsk Regional Museum of Fine Arts, public domain, via Wikimedia commons

If God could save everyone, why doesn’t he? Would it be better for the unsaved to have never have been born? Why would a loving God still choose to create people knowing that they would spend eternity in hell?

For me, there are three things to pay attention to here:

the goodness of creation

the dignity of human freedom

the fact that sin is real and bad and stubborn

If we really take the goodness of creation seriously, then it can never be better “not to have been born.” To exist just is good. To exist is to reflect the divine goodness and to be the object of God’s love. This is better than not existing.

If we believe in some kind of real human freedom (which I think is demanded by the fact that God is love and not force, relationship and not puppet master), then it seems to me that we have to believe in hell, because real freedom includes the possibility that humans will, in freedom, reject God. I hope that, when we all see God face to face, very few (maybe none?) of us will persist in such stubborn rejection, but my next point requires holding open the possibility that we might.

We can’t underestimate the badness and stubborn persistence of sin and the depths of human evil. If an angel could “see” God face to face and turn its angelic back on God (metaphors here, I don’t know if angels see or if they, precisely, have faces, and probably they don’t have backs…), then we should not be surprised that some humans might do so as well. At best, the doctrine of hell is an extension of the doctrine of God, whose love creates free persons and invites them to love. I’m convinced that some version of the doctrine of hell is required for theodicy (understanding God in the face of suffering), because to deny hell is in some way to deny the seriousness, stubbornness, and horror of evil.

These answers are not dogmatic, but they give you a glimpse into my intuitions here and show you that I tend to hope that any residence in hell is not permanent, that there are many possibilities for choosing life in Christ on the other side of death (and not just on this side). The God of love does not send persons to hell who would have it any other way. Hell is not a booby trap; it’s a free human choice. I tend to reject annihilationism (the idea that hell exists for a time but finally fades out of existence), because it seems to me to deny the goodness of the existence of all persons as loved by God. I’d rather a hell with an open door than one that annihilates its residents.

What do we do with the idea of eternal conscious torment?

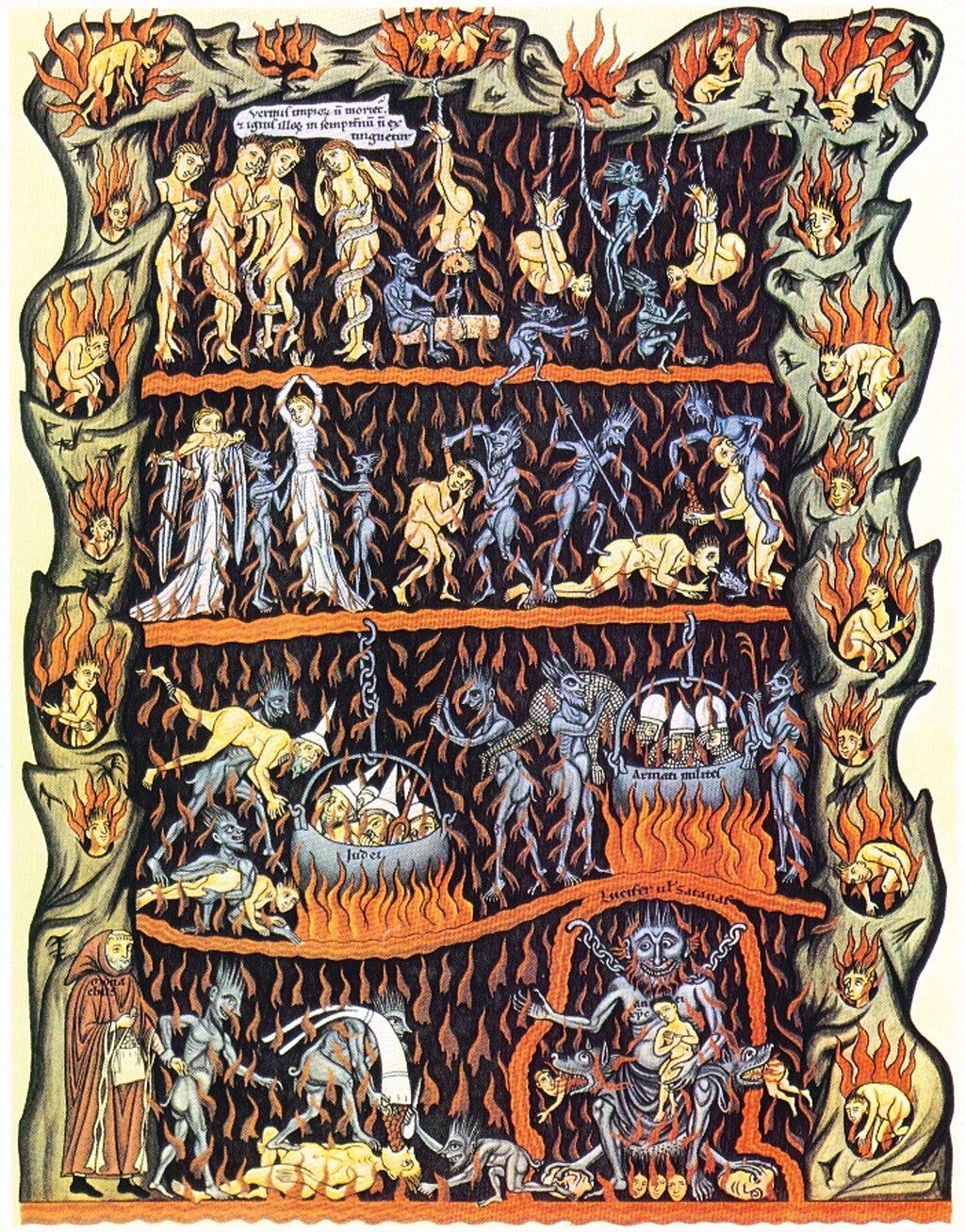

I’m not a big fan of articulating Christian teaching in terms of “eternal conscious torment.” First, it underplays the already/not-yet nature of Christian eschatology, pushing a big old punishment into the not-yet without duly considering how the torment that is the inevitable result of rejecting God is also already real, in the here and now. The idea also tends to encourage mythological ideas about hell, shaped more by cultural artifacts—from great poetry to very bad cartoons—than by scripture. Third, I’ve already suggested that I hope the God who is love will not close the doors on human freedom (though even that sentence presupposes a kind of temporal chronology to the whole thing that I’m not sure we can presuppose.) This I feel sure of: the torment that is rejecting God is freely chosen torment.

What I’m talking about when I talk about “mythological ideas” not shaped by scripture. “Hell,” Herrad of Landsberg, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

A theological question, specifically related to eschatology... are humans ontologically eternal?

No. Humans are finite and dependent. Only God is eternal. God has no beginning and no end. Humans have a beginning, and—if we are to have no end—that will be because immortality is ours in Christ, a gift of grace and not the metaphysical truth about who we are. This does open the door to annihilationism, but I’ve already noted that I’m not a fan.

I’d like to know if you’ve engaged with thought on apokatastasis and if you have an opinion?

I want to engage a lot more in future (that’s a truth and an apokatastasis joke!), but I’m much more drawn to apokatastasis than to, say, annihilationism.

Apokatastasis (loosely speaking, the idea that we keep growing further and further into relationship with God and further and further in godliness forever and ever and ever) seems to fit with the nature of God (eternal, infinite, all) and with the difference between God and humans (finite, created, existing by gift). How could we run out of God?

What exactly is Dwight's eschatological position?

Dwight (my #theologycat, if you haven’t met him, you can do so on my social media feeds) anticipates that Jesus “will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead and his kingdom will have no end.” Dwight also trusts in the “resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come.”2 Because his whole trust is in God, he is confident that whatever part cats play in that life will be just the right part.

At the end of the day, for me, the answer to all these questions is that God is good, God is love, God is the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ who sends the Spirit among us to beckon us toward the glories of kingdom life. God is “patient with you, not wanting anyone to perish, but everyone to come to repentance” (2 Peter 3:9).

Jesus has been to hell for us. That Jesus—together with his Father, in the Spirit—is the God I trust to deal rightly with all questions about hell.

Grace & peace,

BFJ

This piece contains associate links. I’m always grateful if you choose to subscribe, forward, or share.

Love audio books? Try Audible plus.

Amazon Fresh offers grocery delivery on tens of thousands of products – from a complete grocery selection to everyday essentials, toys, gifts and more. Try it now.

Get a 6 month trial of Amazon Prime for students.

Brian Daley’s excellent overview of early church teaching on these matters, The Hope of the Early Church: A Handbook of Patristic Eschatology, comes to the conclusion that there is an eschatological consensus among the Church Fathers, but that consensus is about the resurrection and not about the status, nature, or permanence of hell.

The two quotes are from the Nicene Creed, the best summary of the center of Christian faith that I know of.

Thank you for the thoughtful answers! I always appreciate the ecumenical perspective you include in your writing. Thank you also for the length of time and depth of study that you have committed to the things of God, and then to teaching others. I am better because of it. As well, I received your second edition yesterday and am excited to get to reading it.

Lot's of good questions! How about another? C.S. Lewis' version of hell in The Great Divorce implies that anyone can go to heaven, even from hell, if they want to, that is, if they want to be with Jesus. This fits with your hope that once people see God face to face they might change their mind about Jesus. What do you think of Lewis' approach?