Finding hope to resist the powers

Learnings for today’s American church from yesterday’s South Africa, from Peter Storey + book giveaway

Fellow Pilgrims,

I’ll tell you the truth, I really needed this right now. If you, like me, are desperate for hope for faithful resistance in the face of the principalities and powers, then please don’t skip today’s interview with Peter Storey.

It’s my privilege to publish this interview, in which Sarah Musser speaks with Peter Storey about lessons from yesterday’s South Africa for the United States today. This interview is long. Please, take the time to read it all. I pray it will encourage you to hope, as it has encouraged me.

Peter Storey is the Ruth W. and A. Morris Williams Distinguished Professor Emeritus of the Practice of Christian Ministry at Duke Divinity School. A prominent Christian leader in the church’s struggle against apartheid, he was presiding bishop of the Methodist Church of Southern Africa and served as president of the South African Council of Churches in partnership with Bishop Desmond Tutu. He played central roles in the transition to a democratic South Africa through his work with the National Peace Accord and his nomination by Nelson Mandela to help select members of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. You can learn more here.

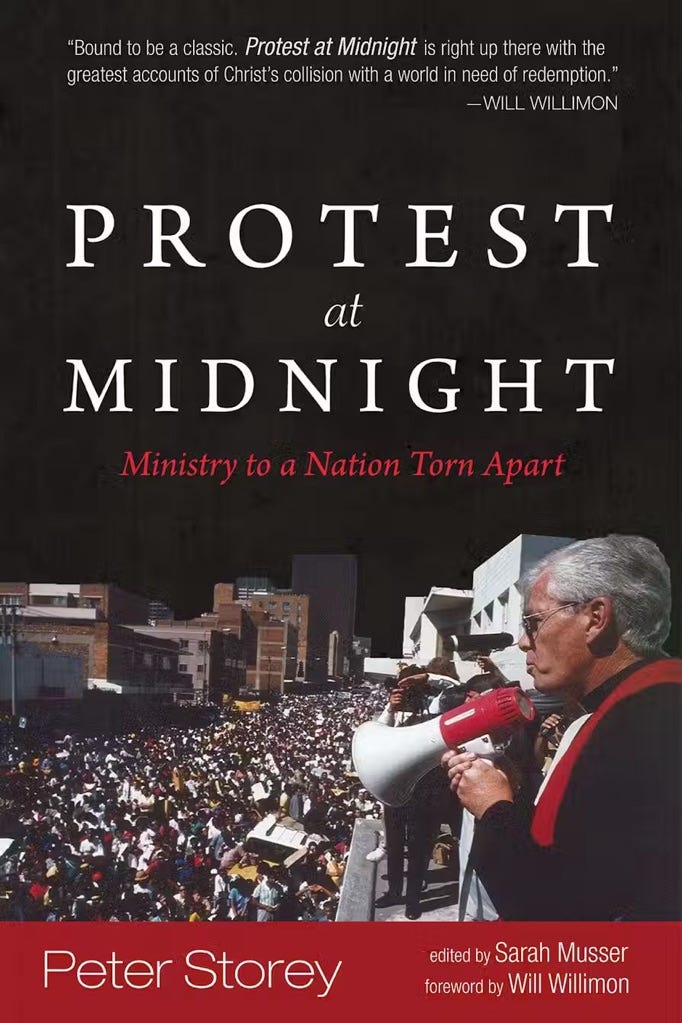

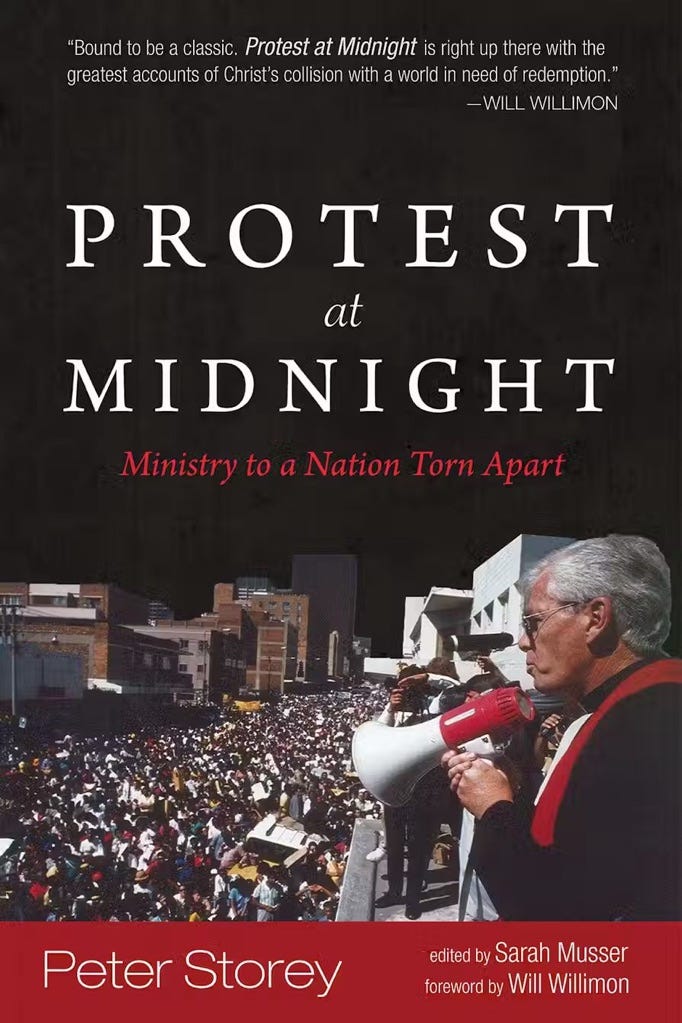

Sarah Musser is Consulting Faculty at Duke Divinity School and works with their D.Min. program as an instructor and writing tutor. She helped Peter Storey revise and edit his memoir I Beg to Differ, published in South Africa in 2018, to create Protest at Midnight, which was published in 2022 for an American audience.

I’ve partnered with Peter Storey to give away 5 copies of Protest at Midnight. To be entered in a drawing to win a copy, share this post or email or go to my social media accounts, where I’ve shared this post, and tag a friend.

FINDING THE HOPE TO RESIST THE POWERS

Learnings for Today’s American Church from Yesterday’s South Africa

Sarah Musser Interviews Peter Storey, February 2025

Sarah Musser: Peter, thank you for this time to talk about your experience ministering during the dark days of apartheid South Africa, and in the days of hope following the fall of the apartheid regime. Would you explain apartheid for our audience to help us better understand the context of your ministry?

The Apartheid Story

Peter Storey: There was a time, of course, in the 1960s–1980s when there were very few corners of the world that did not know what apartheid was about, because it was so high on the agenda of the family of nations around the world, with so many of them joining us in the struggle to end it. But those days are gone now.

So how did my beautiful land at the southern tip of Africa come to be called the polecat of the world, the most racist state anywhere? It was because of a policy introduced by white South Africans to suppress black South Africans. It was called apartheid and it was both unjust and evil.

Before going further let me be clear that, while the label of the “polecat of the world” was entirely deserved by South Africa, no single country has a monopoly on racism. If we turn over a few stones in American history, for instance, we’ll discover that the stories of South Africa and the United States are not all that different. When it comes to racism of different kinds, South Africa and the United States share a particularly shameful history. Let’s look at the many similarities.

The first European settlers in North America and the Cape of Good Hope arrived within a few decades of each other to be met with cautious hospitality from the indigenous habitants. Both settler groups presumed the superiority of their culture—and their religion—and were confident in their sense of manifest destiny, using the Bible to justify their presence as “Christianizing influences.” Both soon fell into conflict with indigenous peoples over land and a divergent understanding of ownership, with settlers trekking inland in covered wagons and dispossessing the inhabitants mostly by trickery or force.

Both in North America and in Southern Africa the settlers enslaved people from other lands for labor and resisted their liberation fiercely. Both fought bloody civil wars among themselves about the fate of either the indigenous people or of the enslaved among them and to preserve what they called “their traditional way of life.” Both built “democracies” that denied the vote to numbers of their citizens. Both emerged as modern industrial nations, dominating neighboring economies and cultivating powerful spheres of influence.

In spite of significant differences, particularly in demographics and in scale, these are impressive parallels.

Now prejudice of all sorts will be found everywhere, but it is when prejudice is linked to power, particularly political and economic power, that it becomes discrimination and domination. The unpleasant truth is that historically, it has been the white races of Europe and their descendants around the globe, who have wielded both prejudice and power most widely and ruthlessly.

In South Africa and in the United States, racism was more than just prejudice, more than simply crude notions of white supremacy. It became systemic, which means that it was so deeply ingrained and such a powerful driver of our cultures that it was intrinsic to the social fabric itself. Beyond simply practicing race discrimination, many of the systems by which we lived and worked actually depended on it in order to function. Every sphere of life—the economy, politics, the criminal justice system, education, health and welfare, the shape of our cities and social life, the practice of religion—everything bore the marks of a prejudiced history, and everything was tainted by it.

When wrong practices become systemic, they begin to bypass the conscience, they become the new normal, giving their practitioners a free pass. So, it was very easy, living with those practices and with systemic racism in both countries, to build a framework of moral justification for what whites were doing to black people, and this is where religion played a role: if some biblical sanction could be found for this deeply unjust way of living, oppressors could live more comfortably with their injustice. In both countries, many churches collaborated by emphasizing certain Scriptures they claimed reinforce notions of white superiority and therefore justified segregation.

In South Africa, white prejudice allied to power became baked into our lived experience by law. We institutionalized our prejudice. We took land by force. We classified people officially by race. Then we legislated residential separation, with non-white people being forced out of places we declared to be “white group areas” and being forcibly removed to those “group areas” chosen for blacks, or mixed race, or Asians or others. We made mixed gatherings between black and white people illegal. We made mixed romantic relationships and marriages illegal. We educated people with different curricula so that white people would always be better educated and more qualified than black people, and having done that, we justified “reserving” certain jobs and professions for white people only.

And so, a web of discrimination was woven into an incredibly strong fabric of oppression, with the white minority living in a bubble of power, wealth and privilege, and blacks, in spite of far outnumbering whites, living in dependence and squalor. As black resentment grew, so the need to suppress them with increasingly ruthless force grew also. South Africa became not just a racist state, but a police state, using methods of repression very reminiscent of Nazi Germany.

SM: Peter, thank you for that background. You touched very briefly on the role that religion played in apartheid. Could you say a little bit more about the role that religion played in supporting apartheid and any similarities that you might see in the United States with the rise in Christian nationalism that many are observing now?

PJS: The role of religion in every society is always both good and bad. In South Africa, first Dutch and then British missionaries had, by the beginning of the 20th century, reached most black tribal and ethnic groups with the Gospel and at least 80% of South Africa’s population belonged to one or other of the historic Christian denominations or black-led indigenous churches.

Christians were divided largely into three major groups in South Africa.

Among whites the three Dutch Reformed Churches (DRC) comprised the largest grouping. These Calvinist denominations consisting largely of Afrikaners—descendants of the first Dutch settlers—with relatively small “daughter churches” for people of color, strictly separated along apartheid lines. No oppressive regime can survive without some kind of religious sanction, and it was the Dutch reformed seminaries that provided a theological “justification” for apartheid. Just as the regressive MAGA movement in the United States today made a deal with most right-wing evangelicals, so there was a very intimate bond, between the DRC and the Apartheid state. The churches gave biblical and theological justification for the regime’s oppressive policies, and because ninety-nine percent of the apartheid government’s members of Parliament belonged to the DRC, the political rulers had a religious sanction to salve their consciences and help them sleep at night, while the DRC were granted preeminence, access, and political power.

Then there were the largely white conservative Evangelicals—Baptists and others—and the Pentecostals, who, by their silence and their lack of interest in matters social and political, effectively collaborated with apartheid. Their interest was in growing their numbers through preaching a half-gospel focused only on the individual’s conversion and personal journey to heaven. If they entered the political sphere, it was only to try and ensure that the South African government should remain “Christian” and protect the Christian religion against others, something that the apartheid regime was very happy to do under the name “Christian Nationalism.”

The vast majority of black South Africans evangelized since 1800 found themselves in what we called the “multiracial” or “mainline” churches—the Methodists, Anglicans, Catholics (all three of these 80% black), Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Lutherans, and so on. Because of their histories of missionary enterprise, and significant black membership, these churches, while not free of discriminatory practices, were deeply engaged in black education and much closer to black suffering.

It was this group of churches, some less willingly than others, who were drawn—first in word and then in deed—into what has been called the Church Struggle Against Apartheid. We had to journey from protest to non-cooperation, and on to holy disobedience and finally onto the streets and into the jail cells of nonviolent resistance. It was a struggle on two fronts, because, at every step of this journey, we had to confront not only the power of the state, but also the sins of our own colonial histories, confessing that though we were multiracial in nature, we had a long way to go before becoming truly multiracial in spirit. It was on this journey that we experienced three crucial sources of strength without which we could not have stood firm against the powers: theological clarity, unity in action and suffering, and the solidarity of the world Church.

First, we were greatly helped by the theology of Dietrich Bonhoeffer and by the witness of confessing Christians in Nazi Germany and others under communism. In the midst of the intensifying conflict, our own theologians, black and white, helped us hammer out a clear theology of Church and State. Some of us called it “being the church under the cross.” Second, we would surely have failed without being ecumenically united in the South African Council of Churches (SACC), gifted with extraordinary leaders as Bishop Desmond Tutu. Third, we were wonderfully supported and resourced by fellow Christians across the world who pressured their governments to declare apartheid a “crime against humanity” and exclude South Africa from normal relations with the rest of the world.

Peter Storey is a South African Methodist minister who is a former president of the Methodist Church of Southern Africa (MCSA), and of the South African Council of Churches (SACC), and Ruth W. and A. Morris Williams Distinguished Professor Emeritus of the Practice of Christian Ministry at Duke University Divinity School.

Christian Resistance – Four Prophetic Priorities

SM: Let’s focus on the topic of Christian resistance. You were a minister of a local congregation, a bishop, and you were also presiding bishop of the Methodist Church of Southern Africa as well as President of the SACC. How did the church resist policies of the apartheid regime, both locally and nationally?

PJS: First we had to be reminded who we were. The collision with the apartheid system was a gift to the South African Church. It confronted us with a moment of truth: “What did it mean to obey Jesus in a nation whose ruling ideology had become an outright denial of his teachings about God, humankind and society?” The answer to that question would decide whether we accommodated to living comfortably with an evil system, or whether we would stop playing at church and begin living into our identity as Body of Christ in the world, whose greatest gift to the world is to be different from it.

For me, as far back as the 1960s, it came down to what I called the four “prophetic Gospel priorities” for the Church to be the Church in South Africa. Those four priorities helped shape my thoughts and actions during the testing decades of apartheid. They helped me in my struggle to stay faithful to the Gospel in a hostile context. I continue to believe in them very passionately and commend them to those who want to remain true to Jesus in the Church/State conflict that is now inevitable in the USA.

The first prophetic priority is to speak the truth without fear or favor.

The first prophetic priority is to speak the truth without fear or favor. A silent church is no church at all. A church afraid to speak the truth for fear of losing members is no church at all. If we fail to name and call out the injustices suffered by the “least of Jesus’ sisters and brothers,” we betray them and Jesus himself. We also fail the powers if we do not point out their wrongs in the light of God’s truth and justice. The task of shining the light of the Gospel into the dark places lies squarely on the shoulders of a prophetic church. Whether from platforms at state and national levels, or in our local worship, fearless truth-telling must be a mark of the church in any unjust society.

Bold proclamation is not enough. Teaching our people to think theologically and helping them to unlearn the civil religion that has captured them is essential if they are to become Christian Americans rather than the American Christians that most are.

Note that, to be faithful truth-tellers, we need as Church, to maintain a “prophetic distance” from all political parties and movements, such that we are free to speak with and into all of them with integrity and without favor. This distancing must not be taken for neutrality: on issues of injustice, we can never be neutral, but our positions are rooted in theology, not political ideology.

The second priority is that of binding up the broken.

The second priority is that of binding up the broken. If we are to resist injustice, we must be in solidarity with all victims of an unjust State. The prophetic church must have a passionate pastoral commitment to those being most hurt. Pastoring them is itself a prophetic act.

This too, can be costly: I was inspired by the advice given me by a German bishop when I asked how I should witness amongst apartheid’s vicious injustices. He had lived under both Nazism and Communism, and suffered under both, and was now making a nuisance of himself challenging democratic Germany. His answer seemed simple: “Pray publicly for the victims of injustice.” I said I was okay with that. Then he said, “Pray for them by name,” and I saw the implications of ceasing to generalize about these victims and to lift up their names and faces. I said, “Yes, we will do that. And then?” He continued, “Go to those for whom you pray.” Here was the call, not merely to verbalize solidarity, but to demonstrate it with your own body. I said, “What then?” and he said, “Suffer.” Binding up the broken is very much part of being a prophetic, risky church resisting the powers.

The third priority is to live the alternative.

The third priority is to live the alternative. A church in resistance must demonstrate in its life the antithesis of what it seeks to resist. It must be a visual aid enabling the world to see and experience the Gospel alternatives to injustice, oppression, separation, and exclusion. Congregations that demonstrate fairness, compassion, unity, and inclusion are living protests because they “sing the Lord’s song in a hostile land.” In South Africa, congregations that defied the apartheid State by becoming racially inclusive were signposts to God’s promised future for our country. They were living God’s future in the now, giving the lie to the State’s propaganda that black and white could never live together in harmony.

They also became targets of course, for bomb threats, police searches and invasions, and worse. However, the more brutal the State action became, the more absurd apartheid was shown to be: ordinary people being harassed for worshiping God together? For visiting the sick together? Feeding the hungry together? Yes, we did lose white members when we integrated—200 of them at the Central Methodist Mission in Johannesburg—but when I looked out on Sundays at the smaller, but so much richer “rainbow congregation” that took their place, I knew that exchange was cheap at the price.

The fourth priority is to find ways consistent with the mind of Christ to either transform or replace unjust rulers.

The fourth priority is to find ways consistent with the mind of Christ to either transform or replace unjust rulers. This means making every attempt to show Pharaoh/Caesar the error of their ways and offering them alternatives. Failing that, it becomes necessary to organize ecumenically, in interfaith movements and within civil society to replace them. If the powers remain intransigent, then being obedient Christians might require becoming disobedient citizens. If we could stay within bounds of legality, well and good. But if not, there are many inspiring examples of nonviolent disobedience to unjust rulers in both Old and New Testaments to offer inspiration for “obeying God rather than men (sic).”

We will not always be of one mind when deciding upon ways and strategies to bring transformation or an end to an unjust regime. In South Africa, questions of economic sanctions and divestment were very controversial but were alternatives to the violence that the SACC refused to sanction. For us, the raising of international economic pressure was a very powerful strategy to bring the weight of world opinion and the world conscience to bear on our regime. Different methods have been found in different contexts, but what they have in common is usually nonviolent mass action of some kind and a determination to transfer some form of painful pressure onto rulers who are causing pain to their people.

Those were the four “prophetic priorities.” They were never perfectly lived out, of course, but they were immensely helpful to me and effective among the congregations I served and at other levels of leadership. Sadly, while so many churches united in the SACC, offering this sometimes costly witness, there were other churches deliberately undermining us— “court prophets,” if you like—who preferred to side openly with the powers or chose cowardly silence. That will always be the case, but the wonder of it all is that, in spite of them, and because of the work and witness of so many committed communities—including the SACC churches—the walls of apartheid crumbled and fell.

Chiharu Shiota (Japanese, 1972–), “I hope . . . ,” 2021. Rope, paper, steel, installation view at König Galerie, Berlin. Photo: Sunhi Mang, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, via Art and Theology.

Holding on to Hope

SM: Your ministry was over thirty years in apartheid South Africa. How did you sustain hope? And what words do you have for the American Church for nourishing hope?

PJS: Hope is so important. After the most recent US election I spent days on WhatsApp, listening to exhausted, confused, depressed and yes, grieving people who knew that their country had crossed a crucial line and still couldn't understand how their fellow Americans could possibly have expressed a will to do that.

And while I came across many Americans who said, “Well, the pendulum always swings back, you know,” there were others with more insight, who were concerned that this time it may not. Be very sure, those representing the new powers in your country are working day and night to shift the foundations of your democracy so radically as to cement their power for many years. You are already watching helplessly as the advances of compassion and justice so hard won ever since the Civil War are ruthlessly swept away by people who want to see them gone.

The question is, who can stand up to that kind of tide? People of moral and ethical clarity and courage, absolutely, but above all, I suggest that it will be those who refuse to surrender their hope. The saying goes that “While there’s life, there’s hope,” but there’s a greater truth: “While there’s hope, there’s life.”

So how do we find hope? How do we nourish it? How do we cultivate it? I have some thoughts here that have helped me.

The first is that real hope is born in the future, not the past. Of everything said by the victorious party in this election, the “Make America Great Again” slogan is the giveaway. They’re all about the past. They appeal to people’s yearning for “what we once were,” or what we think we once were, or more to the point, what our myth-makers have had us believe we once were.

So the question is, what past? I’ve listened carefully for one single new idea in the “Make America Great Again” party, one new idea for the future, and there isn’t one. But the past that the new US rulers are wanting to drag America back into is one of small-mindedness, greed, superiority, exclusion, isolation, and exceptionalism. Think about it: almost every Executive Order fired by President Trump’s MAGA “blitzkrieg” has hurt some group, punished some political enemy, threatened some neighbor, destroyed someone’s job, kicked someone out of the country, endangered someone’s health, reduced someone’s rights or protections, insulted someone’s dignity – all driven by either enmity, revenge, or an obsession with wealth. Where is the hope in that?

Real hope will not be found in turning back our clocks. That’s because God is always ahead of us. Compare the poverty of soul in the Trump White House to the generous, unbounded hope that Jesus taught, hope that strengthens and energizes and sustains us in any struggle because it is born from visiting the future that God dreams for our world.

Jesus called that future the Kingdom, or the Reign, of God, and told us that if we let him change the way we thought and acted, it could happen amongst us. In what we call his Sermon on the Mount, Jesus painted in some of the details of God’s dream of a different kind of society: one where love rules and hatred is banished, where all may enter and none are denied, where compassion and justice walk together, where broken relationships are healed, where war gives way to peace, and death and dying and destruction have passed away … a transformed world. And, as if to say that you can't build that world with untransformed people, he describes the kind of men and women—beatitude people, if you like—who alone will be able to actualize God's dream in this world. The Gospel writer puts that list right at the beginning because new worlds begin with new people.

Our whole faith is built on the certainty that this dream of God for the world will ultimately prevail. That’s why Martin Luther King Jr. was so sure that while the arc of the universe was long, it “bent toward justice.” That’s how, in the darkest days of apartheid’s cruelty, Bishop Desmond Tutu could address the oppressors of his people and say, “Join the winning side before it is too late!”

That’s what Christian worship and preaching in an unjust society should be about: reminding us that the Reign of God—so different than the reign of the powers—is amongst us already, and we are invited to live God’s future in the now. I believe that that's what Jesus was about, and what his Church should be about.

SM: This itself is a key part of resistance, right?

PJS: Absolutely.

A second thought is that hope is sustained by discovering our prime citizenship. I often say that I have two Identity Documents: one affirms that I’m a citizen of the Republic of South Africa, the other is my Certificate of Baptism, declaring that I am a citizen of God’s Kingdom, or Realm. If we are to resist unjust powers, we need regular reminders that our Baptism trumps—pardon the pun—our tribalism. Every oppressive regime in history has demanded total allegiance to the tribe or nation or ideology. Our citizenship in the world-wide community of Christ-followers and the even wider Communion of Saints takes precedence over any mere national identity. That is why, when a Nazi judge demanded of Pastor Martin Niemoller that he swear total allegiance to “the Führer,” Niemoller declined to do so, saying quietly, “The Lord is my Führer.” That is why I say there’s a world of difference between an “American Christian” and a Christian American. So, when I go to church, I expect to come out reminded of where my prime citizenship—my prime allegiance—really lies.

That leads to a third thought: hope is nourished by community. The story of Elijah tells it all. Elijah has prophesied to the Powers, and he’s in big trouble. They want to kill him, so he runs away. He finally gets found out by God in a cave. God says, “What are you doing here, Elijah?” And he answers, “They’re all after me, Lord, and I’m the only one left,” and God says, “Nonsense! I have 8,000 who still have not bent their knee to Baal.”

If our hope is to be sustained and nourished, we need to find those 8,000—or some of them—and join them. They may not all look like us. They may not all believe like us or worship like us, but if they are committed to God’s dream of a nation of compassion, justice, and inclusion replacing one of division and hate, fear and exclusion, we need them, and they may need us. A great danger to the Church in the USA is its pervasive denominational “tribalism” and the weakness of ecumenical and inter-faith ties. We dare not be so arrogant as to believe that “we only are left,” nor so foolish as to think that we can take on the powers without what brave Bishop Budde has called “the Coalition of the Faithful.” In South Africa, one of the joyful gifts of the Church struggle was discovering that it was not ours alone. We learned from others who were paying a much higher price than we had yet done, and it may be that our presence also strengthened them.

Fourth, hopeful action requires dealing with our fear. Regimes of injustice, wherever they are, have only one weapon, really, and that is fear. If we find a way to deal with our fear of the Powers, we disarm them. A question I hear often is, “How do you find the courage not to be afraid?” My answer is, “If you’re looking for courage, you’re looking for the wrong thing.” The antidote to fear is not courage, but love. Perfect fear casts out all love, but perfect love casts out all fear. Therefore, pray for love! Through your prayer life, through your worship, through your immersion in Scripture, and supremely, through the example of Jesus, you will find your love growing for those who Jesus called “the least of my brothers and sisters,” those suffering on the margins, or because they are minorities, or because they are different, or because they’ve been declared illegal and unwanted. And because of how they are being treated, your love will be outraged. And I promise you that outraged love will expel your fear. In the presence of what unjust regimes call power, you will be unafraid.

I believe that to be true and have experienced it to be true. The closer that we live to those who are suffering because of new kinds of injustice that are being inflicted on our society, the less afraid we will be.

Mordecai Ardon (Israeli, 1896–1992) (designer) and Charles Marq (French, 1923–2006) (fabricator), Isaiah’s Vision of Eternal Peace, 1982–84. Stained glass, 6.5 × 17 m. Old National Library of Israel buildng, Givat Ram campus, Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Photo: Hanan Cohen, via Art & Theology.

Hope-Training and a Long Obedience

PJS: There are just two other thoughts I want to pass on. The one is that we need to be trained in hope. I’ve noticed that there’s a group in America that, ever since the election, has a program called “Hope Training.” I like that.

I remember speaking to Filipino Christians who were at the center of the amazing nonviolent resistance movement that toppled President Ferdinand Marcos. They filled the streets of Manila with nonviolent people-power and were so disciplined that, when Marcos sent up fighter planes to come and strafe them, the pilots refused to do so and turned away.

When we met, I asked them, “How did you do it? How did you manage to be so disciplined in your nonviolence, so absolutely determined in your commitment to see an end to this dictator’s rule? And how did you keep your courage, under the threats of tanks and aircraft?”

And they said, “We trained for 10 years. We trained for 10 years to be like Jesus in our facing of the powers.” And I thought about our comparatively puny attempts to train people in nonviolent resistance in South Africa at the time and was suitably ashamed.

They were also training in hope. The more they trained, the more clear it became that the impossible could happen because they were lending their energy to God's dream for the world.

And so, to a last word about hope: hope is crucial because the road may be long. It was Nietzsche—someone I don’t quote very often—who said that for change to happen, “We need a long obedience in one direction.” That says it all. Nothing changes overnight, and so we must be able to stay the course. The Xhosa people in South Africa have a saying when you do something good: they say, “Don't get tired, not even tomorrow.” In that long obedience to God’s dream of compassion and justice, it will be hope, above all, I think, that sustains us.

SM: Thank you, Peter.

Want a free copy of Storey’s book Protest at Midnight: Ministry to a Nation Torn Apart? Share this post or email, or head to my social media and, where I’ve shared this post, tag a friend to be entered in a drawing to receive one of five free copies.

Grace & peace,

BFJ

This piece contains associate links. As always, I’m grateful if you choose to subscribe, forward, or share.

Consider taking a class with me at Northern Seminary, where we talk about theology, doctrine, the bible, and many other wonderful topics. And don’t miss Northern’s partner offerings through Seminary Now, where you can find a streaming library of resources for Christian faithfulness.

At Northern Seminary, we’re currently enrolling a new cohort of the D.Min. in theology degree, starting this June. Want to think deeply about how theology is good for the church? Want to connect your vocation to good theology? Students can work on many possible thesis projects, including but not limited to: examining the relationship between doctrine and questions related to the Black Church, Women in the Church, Immigration and Refugees, Health Care, Wealth and Poverty, Prisons, Catechetical Practice, and Worship.

Come study with me!

We have a new initiative at Northern Seminary - hang out with a theologian for the weekend in a comfortable setting! Join me in May in Mundelein, IL for a weekend discussing my next book on women in Christianity.

LEARN MORE HERE.