Gentle reader,

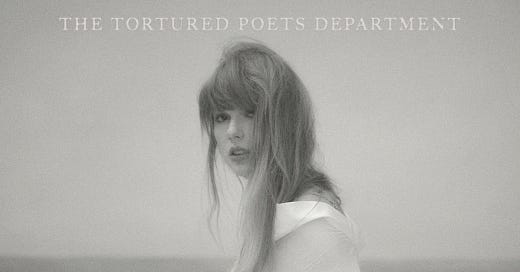

It’s another Taylor Swift moment, bringing with it another barrage of takes on Swift.

I like her music, but my interest in writing about Swift rests mostly in her power as cultural phenomenon. She bridges generations. (I like her; my kids love her.) She’s savvy about culture and about business. And, according to some-Christians-on-the-inter…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Church Blogmatics by Beth Felker Jones to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.